But our main theme at the moment is, what form does thought arrive in the brain? and, to what extent does that determine your method of transcription? To what extent does that mean you have to be a painter or a poet, or to use the typewriter, or a notebook carried around all the time, or, can you sit down at the typewriter between 6 and 9 in the morning?, or what? How do you write? It all depends on how your brain works, how your physiology is. These are considerations in my own verse, which I've noticed in other peoples'. In short-line verse, I write in notebooks (as well as long-line verse in larger school copybooks or big journals). I notice that I tend to separate the phrasing out in the order that it arrives in the mind as words, as phrases. So its like diagramming on a blackboard the way they used to diagram a sentence in high-school (with subject, and a possessive participle under that, and the verb and the adverbs drawn with lines under that, the adjective drawn with lines under the subject and the object with its modifiers). So you get a whole diagram on a page, or a paradigm of the sentence. Generally, I find myself making a paradigm (or diagram) of thought inwards, with all its different parts, and its associations, and sub-associations, and second thoughts, and echoes of thoughts, and additions, and "alluvials", and extra vowels, (as (Jack) Kerouac would say - ((Kerouac's method was to) always end the sentence by adding the alluvials until you finally got the last breath out, continuing to add vowels and consonants, until you finally exhausted the breath itself - because mind will always produce some extra words there). So he said, "Always add alluvials". I think if anybody's got... I don't know where it's printed...

Student: The ABC of Reading?

AG: No, this is Kerouac not Pound, did I say Pound?.. No, I didn't say anything about (Ezra) Pound right now. This is Kerouac - "Always add alluvials" was his specialty. By "alluvials", he meant... what does "alluvial" mean, anyway? - as the alluvial strata of the rivers, what the river has left behind..what the river-of-thought has left behind...

Student: After the flood.

AG: Yes, after the flood of the first thought and the rush and the flood of the first part of the breath, just continue adding on, and you'll get the echo inside the spectral thought that was really behind the thought you expressed for social purposes. You betray your final thought. That's why he (Kerouac) has long sentences very often.

Student: That's the exact opposite of "First thought, best thought".

AG: Well, no, these are the first thoughts being continued, that's all. Put your thought down, but he's saying you'd be a hypocrite with the first thought you put down, so just blindly add what comes on next and you'll get to your first thought again. That's his method.

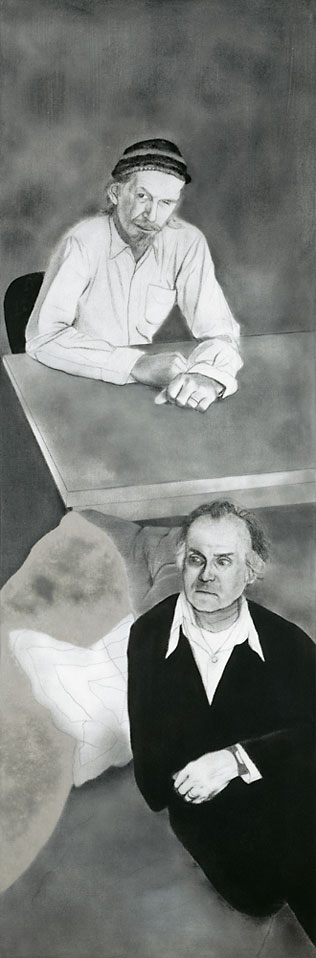

[Jack Kerouac in William Burroughs Garden, Villa Mouneria, Tangier, Morocco - Photograph by Allen Ginsberg, 1957]

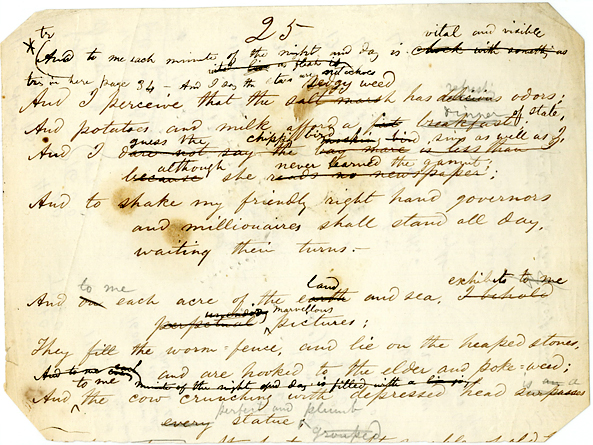

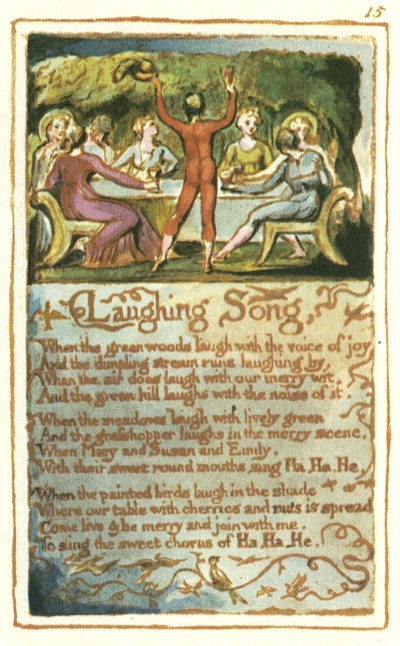

So the units, not of phrasing, but units of mental ideas. I think (William Carlos) Williams does that somewhat, (Ezra) Pound does that. In longer poems in Fall of America, which were dictated into the tape-machine, I measured the lines by the clicks on the microphone. I was speaking into the microphone, not knowing what to say next, shut it off. And there was a little click on the Uher tape-machine (the movement of which was controlled by a hand-held mike which had a stop/start button - the stop/start button determined where the lines were going to be broken off when I transcribed them on the page). And those were units of phrasing as I mouthed them, but at the same time I was mouthing what I could think up in my head, and so the lines are actually a division of mental thoughts, or divisions of the procession of mental verbalizations. I find that a line that echoes in the head, if you mouth it fully with the vowels, sounds pretty good. That often, when you flesh it out, talking it, and pay close attention to talking out the vowels, the musical qualities emerge, that aren't in the head, necessarily (though there are very subtle echoes in the head).What I mean is that the words and phrases that we hear in the head have, implicit in them, vocal densities, tones and rhythms. They arrive somewhat in rhythm, they arrive somewhat with some echo of tone, emotional tone, and with some precognition of the vowel-depth of pronunciation. It's just a question of, when you pronounce it aloud, you make it three-dimensional.. two-dimensional (auditory is two-dimensional). So what I'm saying is one way of measuring the poem on the page is observing the way that mind produces the language, and just notating it down directly, like a stenographer, where there's hardly any work involved. The only revision, or art, or craft, involved there is paying close attention to the mind, and having a long-practiced experience of observing what's coming up. Out of that method of notation, out of that concept of poetry, arises the dictum that (Chogyam) Trungpa worked out in a conversation with me - "First thought, best thought". Because the question is, of all the myriad thoughts in the mind one can choose, how do you know? The mind is thinking six billion things simultaneously - myriad flashes. But, actually, if you think on it and look back a second, the only thing you can remember is what you remember, so you put that down. The only way you can remember, the selection process, is in what you can remember (or mediated between what you can remember and what you can write down fast enough). You might half-remember a long thing, but only write half, and that's all you can get down, and by the time the tail of the thought has flashed away behind the corner, you've got a new thought up there. You (have) to take down the new thought, rather than back-tracking and trying to chase the other thought around the corner. You've got to stop at the stop-light and notate the stop-light. So, there's no way out of the process of accepting the present thought as the thought that is the one you've got to write down (unless you want to be a little dishonest and try to be arty and wait for a better thought than that - but that sets up a feed-back in the brain, and, pretty soon, all you hear is the echo of your thinking - "is this a better thought? or is that a better thought?" - and, after a while, you don't have any thoughts but thoughts about thoughts. So you best leave hands off and take what you can. Yes?

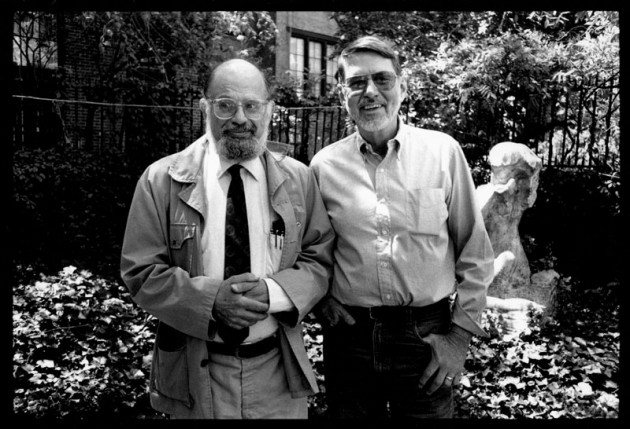

[Allen Ginsberg and Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche in Boulder, Colorado c.1975 - Photograph by Karen Roper]]

Student: What about that process of thinking about your thoughts as you're thinking. That..

AG: "Unrequited love's a bore", as (Jack) Kerouac said , it's boring. Everybody should write two poems about that - and does! - Those are the first two poems everybody writes - about thinking about their thoughts.

Student: What I was thinking was, if you're writing beyond essentially thought that's occurring..

AG: Yeah?

Student: ...those are occurring too. Or...

AG: Kick 'em in the eye and tell 'em to go away, get another (mind to inhabit)! No, it isn't actually what's (generative), it's only a stage of development (like masturbation). And then you move on to something else. It's mental masturbation, that's all. And it's interesting because it's typical, everybody does it, every day. But it's just like in meditation - you move away from that - from thinking about thinking about your thinking - by going back to your breath. So in poetry-mind, you can also move away from thinking about thinking about thinking about writing poems by moving on to what's in front of your eyeball. Look out of yourself. So it's a way of looking out of yourself - "Oh, that's a big tree - I was just thinking about my thoughts - but that's a nice, interesting big tree" - Get on to the tree (unless you want to make out a subject (of) thinking about thinking - but it's more of a drag, and a danger among young poets, because most young poets substitute that - they get trapped in this feedback. Everybody here has been on (it), I'm sure, at one point or other. I constantly get into it in my journals, in one way or another). Even just the process of saying, "Alright, I give up, I'll describe what's out my window" is almost that - "I don't have any great thoughts today, I'll just describe what's on my desk. Well, let's see, here's my hand, and there's my pen, and ink is flowing black..oops, there's a dot, and there's a fly on the page - fly away, tiny mite, in your life" (I wrote a poem like that, reading a book, and a tiny little mite comes on the page - "Fly away, tiny mite, even your life is tender -/ I lift the book and blow you into the dazzling void" - [Allen is quoting from "Returning to the Country From A Brief Visit'] ). Yeah? Someone had their hands raised.

Student: Where's... I know that's a good practice, like trying to write four poems about a door-knob or something...

AG: Yeah.

Student: .... If you try to describe what's out the window...

AG: "Good practice", in the sense of shifting your mind from "I am going to write a poem. I am miserable. Oh misery! Misery is me. Misery in the supermarket. Misery. Misery at my desk.." or something, or, "Vultures circle my desk" (and then going off on a big symbolic thing - "Vultures circle my desk, Nixon's troops are advancing on consciousness", and then writing, what (Chogyam) Trungpa called, "a big resentful poem" about being frustrated, about, about, about..) So, "get off it!" is what I say, like, "shit or get off the pot!", just as, like, "breathe, and get off your mind!", it's just "redirect your energy" - it's easy. A lot of 16-year-olds and 17-year-olds and 18-year-olds make-believe it's not easy. That's because they're clinging to that self-consciousness. And they insist. And it's a form of aggression, sort of. It's defense of territory, and the territory turns out to be a little island-peninsula, a spar of thought about "I am thinking" (which is justified by reading Pascal [Allen means, of course, Descartes] - "I think therefore I am" - so that they say, "Well, it's philosophically correct, so why can't I stay here forever?" - (but) the audience has left the hall. Go out and get a(nother) job, you're no poet!). There are many masked forms of that (particularly, imitations of Pound's verse - which is just reducing everything to just a few sparse thoughts that might reflect on the consciousness of the writer while writing, instead of him forgetting about his consciousness and just looking out). That's another common problem - a constipation of a kind. It's constipation, not masturbation, but constipation. I don't know if anyone around here does very much of that anymore, that kind of writing, but I think it's common (but it's (very) easy to get away from).

Anybody object to that analysis of it, or that take on it? Anybody feel I'm persecuting somebody's (own) ego?