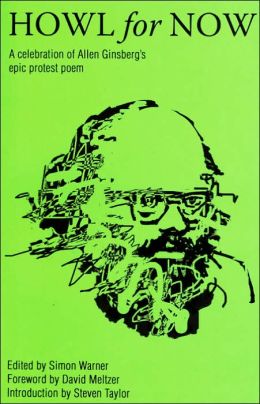

Allen Ginsberg, June 28 1976 class on Spontaneous Poetics at Naropa Institute, transcription of Allen's 1976 summer sessions continues. More on William Carlos Williams. Some of this material Allen has already been through in his extensive William Carlos Williams classes of the previous year (see for example here, here and here).

AG: So we're on (William Carlos) Williams, having focused, finally, on his conception of "No ideas but in things" and some literal fact (as part of his theory of "sticking close to the nose". [Allen reads Williams' poem "Smell" - "Oh strong-ridged and deeply hollowed/nose of mine, what will you not be smelling?..".."Must you have a part in everything?"- The phrase "close to the nose" comes from one of his essays, and when you get that close to your own breath, your own smell, your own senses, and that humorous (of) an acceptance of them, having agreed to work with the senses and having discovered the vastness and tolerance and expansiveness of the senses, the injudiciousness and (the) ecstasy of the senses, there comes a funny kind of self-acceptancy, characteristic of Americans, displayed in Whitman's "I celebrate myself, and sing myself/And what I assume you shall assume,/For every atom of me as good belongs to you/..I find no fat sweeter than sticks to my own bones/ I wear my hat indoors or out as I please." - (Williams') "Danse Russe" (is) complete self-incorporation [Allen reads Williams' "Danse Russe" - "if when my wife is sleeping/ and the baby and Kathleen are sleeping/ and the sun is a flame-white disc/ in silken mists/ above shining trees..."..."Who shall say I'm not/ the happy genius of my household?"] - So there's a psychological correlative to mindfulness, some development of self-reliance and a firm grasp of the ultimate reality of subjective sensation, as being no more than you can bargain for - you'd better settle for that, at least, as evidence to begin with, and then proceed(ing) with a poetics. But this is a sensation with the senses (the six senses at least), mental sensations.

What follows (next) is him...getting up in the morning, early, as a a doctor, and going out and looking around in the streets of northern (New) Jersey, turning his attention outside of himself. [Allen begins reading from "January Morning, A Suite" - "I've discovered that most of/ the beauties of travel are due to/the strange hours we keep to see them:/ the domes of the Church of. the Paulist Fathers in Weehawken/against a smoky dawn - the heart stirred -/ are beautiful as Saint Peters/approached after years of anticipation."] - So he goes out into his own town and takes note of little delicate details - "- and a horse with a green bed-quilt/ on his withers shaking his head/bared teeth and nozzle high in the air!" (that's very similar to Reznikoff's little details) - [Allen continues to quote from "January Morning" - (from VII) - " - and the worn,/ blue car rails (like the sky!)/ gleaming among the cobbles!" - (from VIII) - "and the rickety ferry-boat "Arden"!..." - (from X) - "The young doctor is dancing with happiness..".."He notices/ the curdy barnacles and broken ice crusts/ left at the slip's base by the low tide/and thinks of summer and green/ shell-crusted ledges among/ the emerald eel-grass!" - and (from XIII) - "Work hard all your young days/ and they'll find you too some morning/ staring up under/your chiffonier at its warped/ bass-wood bottom and your soul - / out!/ - among the little sparrows/behind the shutter."] - So when he finally thinks of "What is soul?", what happens to death?, it's nothing but objective activity detail - sparrows out behind the shutter, instead of a horrific fantasy based on words that would give him a bum-kick. Except, also, the practical fantasy of, there he is, flopped down in his furnished room on the rug, his head rolled under the chiffonier (a large wooden chest with drawers where you keep your clothes) . Yes?

Student: What's "horrific"?

AG: Pardon me?

Student: Did you say "horrific"?

AG: Horrific. Horrible. Miltonic variant of "horrible" - "horrific". Nice word. [Allen continues with the poem - (from XV) - "All this -/ was for you, old woman./I wanted to write a poem/ that you would understand./For what good is it to me/if you can't understand it?/ But you got to try hard -/ But -/ Well, you know how/the young girls run giggling/ on Park Avenue after dark/ when they ought to be home in bed?/ Well,/ that's the way it is with me somehow." ] - So there's detail and there's humor in relation to his own self, and there's the beginning of a kind of bodhisattva attitude towards the hearers outside the canon of ordinary poetry, or traditional poetry. These are now actually written for his wife, his mother(s), his neighbors - poems that actually can be communicated to ordinarily-considered non-poetic people, because they're using words made out of the materials of ordinary conversation, and they're dealing with matters that can be apprehended by eyeball and ear and senses, so that there's common ground and common territory. And it's very clear, clean, territory, because the words have all been washed clean of other associations and the perceptions have been washed clean of ideological reference, and there's nothing but the thing itself sitting before him, the natural objects, their own adequate symbols of themselves. "All things are symbols of themselves" - another Gnostic thought - or it's a Tibetan Buddhist thought - "All things are symbols of themselves" or "No ideas but in things", still. So that leads to that poignant moment in (Williams' poem). "Thursday"[Allen reads Williams' "Thursday" - "I have had my dream - like others-/and it has come to nothing, so that/ I remain now carelessly.."..."..and decide to dream no more."] - So that kind of (resignation) intersects all common newspaper-consciousness. Old guys in the saloon "gave up". Williams gave up. Buddha gave up. Christ gave up. Everybody gave up and found themselves on Earth - to be perceptive, to do what? - In this case, to continue trying to clarify the language and create little clear rhythmic structures within the language, drawn from the speech of his towns-people. He could communicate to them in a familiar way - be so subtle that they wouldn't notice it was poetry. And with that also came a great deal of compassion - social compassion - noticing how hard-up people were.

.jpg)