Remembering Jack – 1 Allen Ginsberg, John Clellon Holmes, Gregory Corso and Edith Parker Kerouac

We've been featuring recently (hereand here) some readings from the 1982 Naropa On The Road Conference celebrating Jack Kerouac. This weekend - a panel discussion. Allen explains: "Our idea was to go through, each one tell how we first met (Jack) Kerouac, center on that, and then, if we have enough time, to go around again or combine it with one literary hit off of Kerouac"

Participants are Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, Peter Orlovsky,Michael McClure, John Clellon Holmes,David Amram, Fernanda Pivano, Ann Charters,andEdith Parker Kerouac. Periodic shout-outs for Carl Solomon,Herbert Huncke, Lawrence Ferlinghetti,Carolyn Cassady, Diane di Primaand Jan Kerouac to come up to the podium and speak remain unanswered

The tape begins with about five full minutes of announcements (including announcement of a meditation session - "the last one was very successful, with about..about a hundred people came, so the more the merrier") before Allen takes over (Allen and Gregory Corso are the de facto co-ordinators of the event).

The complete tape may be listened to here.

AG: So I’ll start. Our idea was to go through, each one tell how we first met (Jack) Kerouac, center on that, and then, if we have enough time, to go around again or combine it with one literary hit off of Kerouac, See, Edie Parker knew Lucien Carr from drinking at the West End (bar). I was living across the hall, on the seventh floor of the Union Theological Seminary, in New York City, near Columbia (University), during the war, 1944, when the dormitories were filled with young navy trainees, so that the college students were bumped and they had to go live at the Union Theological Seminary dorm, and I heard Brahms, Trio number 1, coming outside of Lucien’s door, the music, so I knocked and saw Lucien Carr looking like an angel, and made friends, and a few days later, he had met Edie Parker at the time (she was) called, at the West End bar at 113th Street on West End (Avenue) and Broadway, where all the college kids drank, and Lucien told me about this guy he had met who had just come back from the ocean, was a sailor but wore a black leather jacket and who had a ..who was a poet, and a novelist - and that was the first time I ran into someone who was a writer - because I was going to Columbia University and there were no writers there.

AG: Nobody boasted of being a writer in 1944, in the summer of 1944. There was no one who claimed being a writer or a poet. So I found out where he lived, (and I think it was an apartment that Edie Parker’s mentioned somewhere or other this week), right off Columbia University on 105th.. (no,) 118thStreet, climbed up, knocked on the door. I think Edie or Jack opened the door, and he was sitting there, eating breakfast, wearing a t-shirt and chino pants, and he was amazingly handsome, like really young (I don’t know how old he was at that point, but..when was he born?)

AG: So he’d be twenty-two years old - really sharp-looking, like dark, handsome, deep deep deep eyes, (beautiful in a way, as Jan Kerouac is quite beautiful right now at a little older age) but I remember eyes and (a) handsome straight nose, so I immediately dug him as a sort of a..well, as what? - not as a (guy) – I’d never been laid, anyway, see, I was a virgin and completely innocent and scared, and nobody knew I was queer, to begin with. So I was there under false pretenses as some kind of studious intelligent interested student going up to meet him for what reason? - well, he couldn’t figure it out and I couldn’t figure it out, and he was eating his eggs. And so I said, “well, um..bla-bla-bla”.., and he said "bla-bla-bla”. And then he said.. something, and I said. "well, discretion is a better part of valor” (which is something I heard from my father, constantly telling me “discretion is a better part of valor” – and I hardly knew what it meant! - except it was something that I would drop into the conversation when I couldn’t think of anything to say and I wanted to appear smart because I felt like a complete fool). So he gave me a funny look that I’ve seen in movies like [Allen mimics], that he gave Steve Allen [on his tv show] like..a grimace..a side--grimace of the mouth meaning “What is that?, What’s that for?” and he decided that I was..I guess he must have decided that I was a New York Jewish Intellectual. Then, that day..

John Clellen Holmes: Pretty good take!

AG: ...that very day, that same day (or another in that same week, see, it’s melted into my memory as the same), I had to move from Union Theological Seminary to.. following Lucien Carr who had moved to a hotel on 115thStreet. So I decided I’d move out and go to the hotel..and I asked Jack to help me move or walk me down (so we had to walk down the Columbia campus from 118th to 125thStreet and through the campus and up seven flights, down a long wooden corridor, in a Theological Seminary setting, to an arched brown open door, where I brought out my valise.. so I took my valise out and turned to the door and closed the door, and said, “Goodbye door”, and Jack said “Ooh?”, and then we walked down (to) the rest of the corridor, and I said “Goodbye corridor”, and he said “Mmm”. And then I said, “Goodbye step number one, goodbye step number two” (because we had seven flights of steps to go down). And he said, “What do you mean?” And I said, “Well, I know I’ll never see it again in the same body (or if I’m in the same body, it’ll be years, twenty-five years later, or forty years later , and so it’ll be like walking back into an ancient interesting classical dream”. And he said, “Do you think like that all the time?” And I said, “Oh, I always think like that…. Nobody else does but me, I think, maybe", or "does anybody else ever think of those thoughts?"- like one day, I remember, when I was walking home from the Fabian Theater in Paterson, I was passing by the hedges by the church near Broadway and Paterson, and I thought, “Gee, I wonder how big the universe is? – and at the end of the universe is there a wall? and what would the wall be made out of? rubber? – but if it was a wall made of rubber would the wall of rubber go on then for another billion miles? - and what would come after the rubber? ...so where does… how do you.. how do you finish.. what is the end of the universe?"

Gregory Corso: I know, Al, I can tell you. It’s spherical like a bubble (you know, like your water bubble) but there’s another little bubble that’s attached to it.

John Clellon Holmes: Is that it?

AG: Yeah.. that means I can…

GC: Water bubbles

AG: Like that?

GC: Water bubbles, spherical, and then there’s another one attached to it, a little one attached to it.

AG: Well, I didn’t think of that at that age. So those were the kind of questions that Kerouac and I both thought about, and our first rapport was over the fact that both of us said goodbye all the time to the space where we were at that moment, realizing that the space was floating in the infinite universe, and that the universe is changing, and that we were transient, interesting, charming phantoms, appreciating the space around, and that we were only there for that hour or two and so we were constantly saying “goodbye”

Gregory Corso: So that answers that then. When was that? early?

AG: John Holmes (next) then

Gregory Corso: John Holmes [John Clellon Holmes and Jack Kerouac]

John Clelland Holmes: Well.. Is this microphone is working.. can you hear me? Yeah - I, in the late Spring of 1948, I heard about somebody called Jack Kerouac. A friend of mine who was then working for, of all places, the New Yorker magazine, knew Allen – Ed Stringham– and through Allen, he heard about somebody called Jack Kerouac, who had written, and almost completed, an enormous novel that weighed forty pounds or something! =- So Stringham told me and another friend of mine, both of whom were aspiring novelists, about this, and we were quite eager to meet this guy, and the long weekend of July 4th ]of that year, my wife was out of town, visiting her family, and (Alan) Harrington, the other guy, came to me and said, “Ginsberg called, and he and somebody else were throwing a party up in Russell Durgin’s apartment, or - [turning to Allen] - was that your apartment? – it was Russell’s I think

AG: What year is this?

JCH: (19)48

AG: (19)48 and what date? July?

JCH: July

AG: I was probably living there because I took it for the summer

JCH:I think that you were living there but I think it was Russell’s apartment

AG: Yes, it was Russell’s apartment that I sub-let for the summer

JCH: So…that sounded good and the..I think, also, you, Allen, had told Alan Harrington that Kerouac would be there.

AG: And I think (Herbert) Huncke was living there at the time.

JCH: He wasn’t there that night

AG: OK

JCH: Sorry! – So off we went, it was hot, sweltery, got into Spanish Harlem, the streets were full of the smell of..the great smell of beans and there was plenty of music coming out of all the windows. And here.. we just hit a building that was just like any other building, and up we went to about the fourth or fifth floor (I can’t recall, it was up top) and the closer we got to it, the noisier it became, and the music was not.. was not Latin music so much as it was jazz. And in we went, and I met Allen first, who was hosting it – [to Allen] - (at least you acted like a host), and there were a lot of people (I didn’t know any of them, didn’t know any of them, Lucien was there, I can’t remember any of the others, the oth ers were kind of, a kind of conglomeration of Columbia students- I don’t think John Hollander was there, but he was part of that crowd ). And Allen, as you probably all know who know him, is extremely generous and saw that we had beer (we brought some beer along anyway) and introduced us to a few people, and it was one of those typical poverty-stricken, tenement houses (all the rooms butted up on one another, there was no hall, you headed into the kitchen), all the windows were open because it was a hot night, and the beer was flowing. And I went into the other room that I think you probably used as a living-room, which was where Russell had his books.. (no, (Herbert) Huncke lived there later, I never met him), and I did what I often do when I’m in a place where I don’t know or don’t know anybody, I kind of stood around and I checked out the guy’s books. Well they were primarily seventeenth-century and eighteenth-century English poets, and very fine editions as I recall. And then I looked over and there was a couch against one wall and there was a guy I’d never met, who turned out to be Jack.

I was just, like Allen, struck by his looks, immediately (undoubtedly, for many of the same reasons that you were struck by them). He was an arresting man to see, he was incredibly handsome, but beyond that he was a.. there was something in his face that was.. that you couldn’t take your eyes off. There are certain movie stars that are like that, but not necessarily good actors, but the camera loves them, and you look at them. So I went over and he was very shy and withdrawn, until he learned that I was a writer too. Then he opened up a bit but both of us didn’t quite know what to make of one another. And you (Allen) [turning to Allen] hustled in and did what you so often kindly do, which is to make two strangers feel, with each other, feel at home, and so that’s how I met him. A week later, or about two weeks later, his novel was given to me, he gave it to me, it was in a huge doctors bag, as I recall (and it did weigh about forty pounds – it was just about like that) and I read it with some interest, although I knew nothing about the man, except that he’d struck me as being somebody that I wanted to know. Of course, reading the book astounded me, and, almost immediately thereafter, he came by to my apartment for something, and we..and we just saw one another from then on. That’s the first night.

AG: Yes, I’d completetly…

JCH: It was, it was the novel.

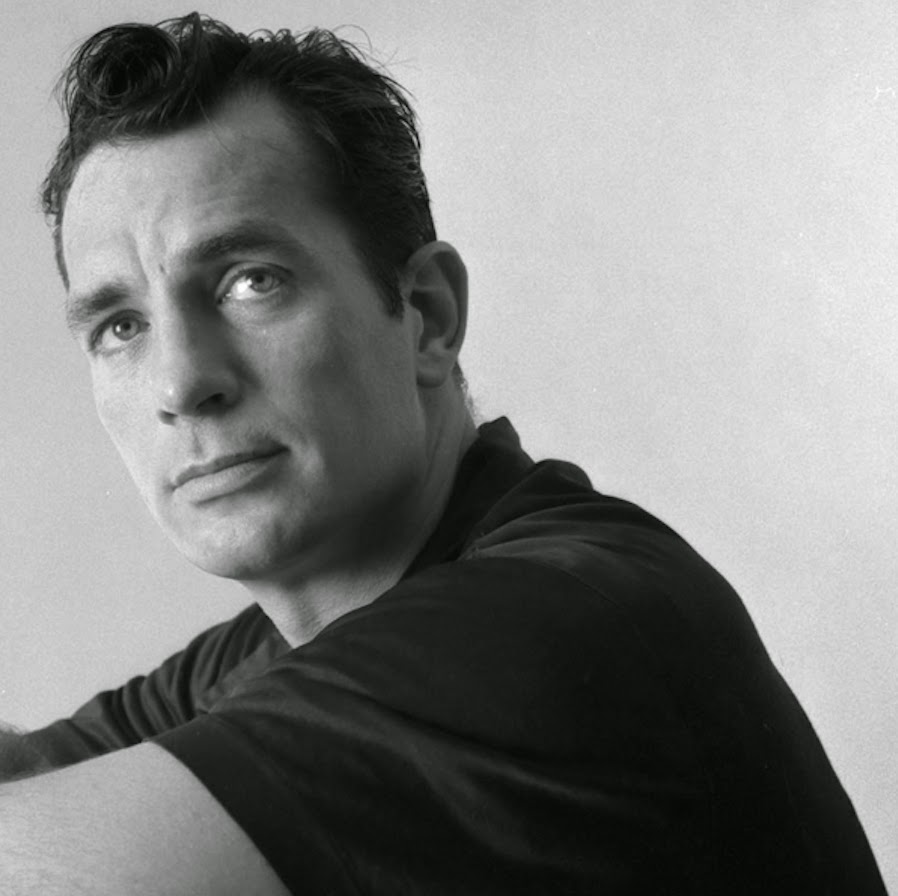

AG: You know, I’d completely forgotten about that party till he mentioned it now [Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and Gregory Corso - Photograph by Bruce Davidson]

GC: Right, I’m the third one then? - I’m 1950? I can be 1950 or 1949 the middle of (19)49, towards its end, because I had come out of prison…at the..towards the end of (19)49, and that’s when I met Allen Ginsberg and, through Ginsberg, met Kerouac…[commenting on the mic] - is this working?

AG: You could take a a little distance..

GC: OK… I met Allen in a lesbian bar in Greenwich Village. I was in this lesbian bar because I was what? nineteen? going on twenty. I was in this lesbian bar because a friend of mine was doing caricatures of people there, an artist, the first artist I ever met, his name was Emmanuel Diaz. Anyway, one night Allen comes in, and now I don’t know if by this time he’s out of the closet because you say when you met Kerouac you were what? virginal? Were you a virgin when you met me?

AG: No..nineteen fifty? no.. I don’t really remember now.

GC: Alright .. So I had a good-looking young Italian face, you know in 1950, twenty-years-old, so I figured that’s why he came up and spoke with me, but, I mentioned I was a poet and I had my prison poems with me, and Allen said, “I’ve got to introduce you to the Chinaman, then”. And the Chinaman in his head at that time was a good minor poet, who was Mark Van Doren, who was his teacher at Columbia. So he first brought me to Mark Van Doren. And after Mark Van Doren was Dusty Moreland, and this is how it worked. I told him I was living on Ninth Street and Sixth Avenue and there was this girl I’d watch go to the bathroom and have sex with a guy and all that, and I’d jerk off to it. And he said, “Where? what apartment?” and I’d tell him and he said, “Well I’m the guy that’s going to bed with that girl! - And so I said, like wow! then you can bring me up there and introduce me, and so he did. So that was a beautiful coincidence, right? that Dusty Moreland. And I think maybe a month after that, a man in a white CIO cap? - did he wear? CIO? from the merchant marine, a white shirt ,white pants – who’s apartment? there was a little room there on the side – was it your… AG: NMU - NMU cap – National Maritime Union?

GC: Yeah but I think it was the CIO that he belonged to.

AG: Yeah.

GC: But, alright.. what house did I meet him in when you brought me to introduce me to him?

AG: To Dusty or to whom?

GC: It wasn’t Dusty’s house.

GC: It was someone’s house, I don’t think it was yours

AG: Right near..Ninth Street?..Where was it?

GC: It was in New York City..

JCH: Is that the closest you can get!

GC: Anyway.. the closest… and it was you and he alone and you introduced me to him

AG: I’m trying to figure out where that would be. Henry Cru was a friend of Jack, who had a place in..on..

GC: Did you go out the window on(to) a little roof?

[Audience Member]: (Twelve Street - Edie's place on Twelfth?)

AG: Gee..I…

GC: Or maybe that's the place, I don’t know

JCH: No, Edie wasn’t on the scene then.

GC: No, this is 1949, 1950. Anyway, ok..[Audience Member] (Seventh Street?)GC: No, nobody lived there till so much later. Come on, not Seventh Street not Sixteenth Street either, but anyway a place in New York City. And we hit it off right away Kerouac and I (there was some kind of warmth that they (Ginsberg and Holmes) both hit on was his features. I had him in a poem once ["Elegiac Feelings American"] with Clark Gable’s hands ["How so like Clark Gable hands.."]. That was the best way I could describe him, that way, like a movie actor, and very strong, you know Clark Gable had hairy hands, so did Jack. But did I tell him I had poetry, I wrote poetry, that was the ball-game. He had asked me what poetry was and I told him it was everything, you know. So that’s the first encounter with Mr Kerouac. Was it the end of (19)49 or the beginning of (19)50, I don’t know..I can find out..I can find out when I left prison. JCH: I think it was (19)50. I met you soon after that

GC: Did I meet you the same year?

JCH: I met you in the early (19)50’s

GC: Early (19)50’s

JCH: Yeah

GC: That’s what I mean, it could have been late 1949 or …

JCH: It couldn’t have been (1949)

AG: I don’t remember your meeting with Kerouac. Do you?

GC: Yeah, you brought me there.

AG: Do you remember the conversation?

GC: Yeah – “What’s poetry?” because at that time, as a poet. I told him it was everything.

AG: And what did he say?

GC: He looked at me ..

![]()

GC: Yeah here she is - You’re the earliest one to know him man, you’re 1940

AG: So maybe..why don’t you come down and tell your story. What we’re doing is giving little..just short brief hits, how we met, Edie.

GC: But both of us met Kerouac through you.

JCH: Yes, right

GC: Allen was the catalyst of that

JCH: And he’s still doing it...

AG: Now Edie is..Edie was the catalyst for an earlier meeting with me and Jack and (William)Burroughs and Lucien Carr. So if you’ll just sit over here and give us a little description of that, Edie, we’ll get that.. (How did your lecture go?… come on, sit down..taking big bows!).. then we’ll call Nanda (Pivano) back for the Italian.. connection. So the question is how did you first meet Jack, first time?...

[Edie Parker Kerouac (1922-1993)]Edie Parker Kerouac: I first met.. I first met Henry Cru. I first went with Henry Cru, who lived in my grandmother’s apartment 438 West 116t Street, and his mother and my grandmother were friends, and me and Henry Cru liked each other, and he was going to Horace Mann with Jack (Kerouac), and he wanted me to meet his best friend. So he took me and he asked us out to lunch and we went to a New York delicatessen which I’m not used to and I sat down and immediately had six sauerkraut hot dogs and from that time on he fell in love with meAG: You said that the other day

EPK: I know and I…

GC: What year was this?

EPK: 1940

AG: That early, ok. Do you remember any of the first conversation at all?

EPL: I don’t think he said much at all.

AG: Yeah

EPK: Well I tell you..

AG: What was the first conversation you can remember?

EPK: To me?

AG: Yeah

EPK: Oh..

AG: Or with anyone?.. (It’s hard, actually.. thinking about..)

EPK: Impossible.

AG: Yeah

EPK: I’ll tell you what he did, Allen. He liked me. So the next day he wrote me a love letter

AG: Ah!

EPK: ...on one page

AG: So fast!

EPK: He delivered it by hand and he gave it to the bell-boy who brought it up to me and I was.. it was gorgeous. I wish I’d..

AG: What did it say?

EPK: Oh, oh my god, he called me his birdnote and his..

AG: His what?

EPK: Birdnote. He always called me his birdnote..

AG Bird note?

EPK: Uh-huh. and he talked about when he first met me that I walked on Amsterdam Avenue and that I fed a horse that was a beggar’s horse, a junk man’s horse, and he talked about that and he talked about that if I went into the deepest deepest part of the forest under the (den) where there was the deepest part of the forest, and I lifted up a rock, there I would find his heart.

AG: Hmm.

EPK: I remember that.

GC: Wow!

AG: And do you remember what book he was writing then?

AG: Yes..now do you remember anything about that book?

EPK: I’m really not kidding you Allen. I think it’s in the attic of my house.

AG: You have it?

EPK: Yes

AG: (Do) you have The Sea Is My Brother

EPK: Yes, I think so.

AG: That’s a revelation. The long-lost manuscript!

EPK: I..when we moved from one house it was on the top of a shelf and it was thick like this and my sister and I would recall reading it..constantly.. but it did go on and on – and on and on and on

AG: That was his first novel, which he was writing when he was a sailor going up the.. around..sailing around Greenland.

EPK: Yeah

AG: That was his big symbolic novel while he was readingThomas Mann –The Magic Mountain.But The Sea Is My Brother is like a..sort of classic title, and it was his first really Romantic prose, and it was the first extended work before The Town and the City. GC: Eighteen? Eighteen years old?

EPK: Yes. Yeah. He never.. As long as I knew him he never stopped writing, never. He was always…

AG: Well how did you get that manuscript, did you just… he left it with you?

EPK: No, he lived with me in Grosse Pointe and he handed it to me. AG: But when he visited, when you got married and he visited there, he just left it there?

EPK: Yeah,that's right, he left it there and he lost it. That’s where the picture is in my a little book of the merchant marine with the white hat. It’s in my little book. And by the way, Gregory, I have a picture of Dusty Moreland.

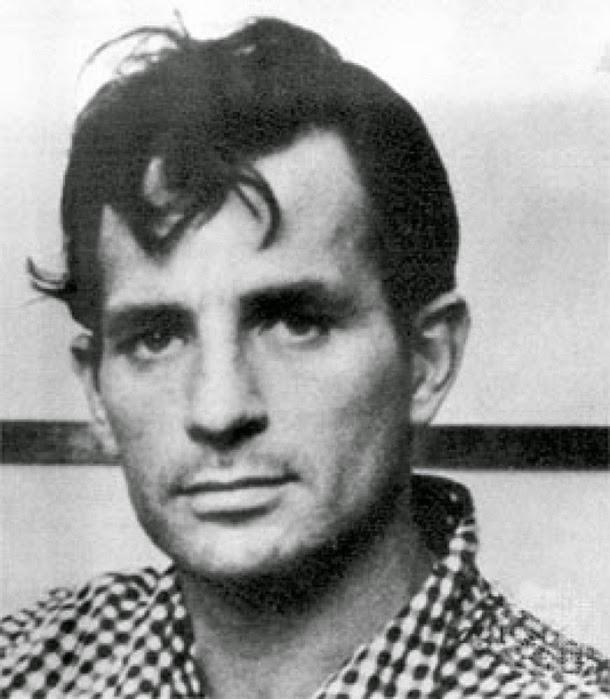

GC: Oh great! Yeah, beautiful. My first lay when I got out of prison.

JCH: She was a knock-out too

AG: Listen, Dusty..I called Dusty to invite her to the conference and she was outraged at the way that I had referred to her in some letters that were published and felt that I was wrong in not changing her name

GC: Yeah, I don’t blame her

AG: So she’s sensitive.so..

EPK: John Kingsland just gave it to me

GC: I want to see the picture when you have a chance..

[Dorothy "Dusty" Moreland]

[A version of this text appeared in Beats at Naropa - An Anthology (edited by Anne Waldman and Laura Wright, Coffee House Press, 2009]