“Why me?” I asked, when there were so many big-time journalists who would jump at the chance. Richard—whom I had only met a couple of times—replied that they weren’t as sensitive as I was.

I said yes, with trepidation: this was a high stakes piece (was I up to the task?), and my newspaper experience included its share of botched edits and misleading headlines. I was relieved when The Voice signed an unusual contract with Allen, ensuring that he would be able to offer notes on the piece and have veto-power over the headline.

The beginning of the 4,500-word article filled the back page of The Voice’s July 5, 1976 issue, under the headline “Allen Ginsberg Sees His Father Through” (a banner at the bottom of the page read “David Mamet: Best New Playwright of the ‘70s”). Louis Ginsberg died on July 7. I received a card from Allen, letting me know that Louis had been well enough to read most of the article. Among his last words were, “I have read enough.”

As far as I know, the piece has never been reprinted or digitized, so today (June 4, 2015), exactly 39 years after my visit with the Ginsbergs on the day after Allen’s birthday, I keyboarded the text. I made no changes (no matter how much I was cringing) other than to correct a few typos.

Allen Ginsberg has been spending a lot of time in Paterson, New Jersey, lately. He stays in a spacious, softly-furnished three-room apartment in a modern brick building in the suburban East End of the city. The telephone—like the one in his Lower East Side apartment—needs frequent attention, wired into Allen’s network of involvements, which lately have included recording an album and touring with (Bob) Dylan. But much of Allen’s attention these days goes to his 80-year-old father, Louis, who is seriously ill with a malignant tumor. At the Paterson apartment Allen shares with his second wife, Edith, Allen is mostly a son, giving care and company to his father. On June 3, he was 50. Louis Ginsberg has lived in New Jersey all his life, teaching English at a Paterson high school for 40 years, which overlapped with 20 years teaching nights at Rutgers. Louis Ginsberg is also a poet, but, unlike his son, he used words as flesh for skeletons of traditional meter and rhyme schemes. Although Louis is widely published, including three books and numerous anthologies, he is best known among contemporary poetry audiences for his readings with Allen over the last decade. A Ginsbergs reading often climbed the media scale to “event” status, a rarity on the poetry scene; perhaps only Russian poets reading at Madison Square Garden have attracted more press coverage. It was a natural and often oversimplified story: old and young, square and beat, meter and breath. Father and son. Their first reading, for the Poetry Society of America in 1966 in New York, was billed as a “battle,” and police were actually called to stand by in case the crowd got unruly. Allen Ginsberg now finds the police incident funny, but at the time, “I was really pissed off! Calling the police? My father and I reading, and they’re calling the police? Undignified! There was a tendency to stereotype, and to exploit the situation as conflict rather than harmony which would have been more helpful socially, and probably more aesthetically pleasing." And there was often humor in their byplay which eluded the media. "Many think we bridge a generation gap," says Louis. "We've had many wonderful times."

Now that Louis is mostly confined to his apartment, Allen stays by his side as much as possible, and there is more harmony than ever. It would be tempting to think of their current relationship as the Son Comes to Terms With His Sick Father, but the son never strayed too far, and they are merely continuing a process that has been going on for, well, a generation. A process which accelerated when they were on the road together—"When we traveled, we also traveled inside each other," says Louis.

They used to argue about the Vietnam War, until Louis changed his opinion around 1968. Allen had thought it was just a political disagreement until he overheard his father attacking the war to someone else, and Allen realized that their clash also had something to do with their relationship. "It was a personal ego conflict between us of who was going to be wrong and give in." This peaked in an argument during a car trip when Allen got so exasperated that he blurted out, "You fuckhead."

Louis didn't respond verbally, but Allen remembers a quizzical fatherly look of, "you'll feel badly later that you spoke to me like that." Louis knew that "when Allen lost his temper at me he'd usually call later to apologize."

Allen did regret his harshness, but "it sort of broke the ice in a way. It was so outrageous that it was human and funny. It was the intensity of love; I was so concerned about communication with him, that we be on the same side, that I was really like going mad and crying and yelling at him." Eventually Allen became "more gentle," giving his father "space to change."

And now, communication-through-gentleness is the motif that decorates their relationship. Allen describes it: "As his life draws to a close, there's a possibility of total communication and poignancy of our being here this once and realizing that it's closing. It makes all the poetry of a lifetime come true, at its best. It's a good, open space, very awesome and beautiful." Both agree that they're more open with each other than ever before; their closeness was evident during the course of a day I spent with them in early June.

***

Edith Ginsberg gets a chance to I go out with her friends when Allen is around, secure that her husband is being well cared for. When Louis says he is thirsty, Allen is halfway to the kitchen before Louis has told him what he wants to drink. Louis tells me that Allen is a "wonderful son, waits on me hand and foot," and they spend their time talking, about such things as "death and illness, elemental things." Allen returns to the living room with a glass of ginger ale for his father, and adds, "olden times, modern times, poems that influenced our youth." On the day of my visit, references from father and son came from the likes of (William) Wordsworthand (John) Milton, two poets who had a strong presence in Allen's childhood along with the lyric poets of Louis Untermeyer's anthologies (including Allen's father). While young Allen would be lying on the floor reading such comics as Krazy Kat and The Katzenjammer Kids, Louis would walk to and fro quoting poetry (perhaps a graduate degree could be built on the combined influence of Milton and Krazy Kat on the poetry of Allen Ginsberg). Louis recites, from memory, a section from"Paradise Lost" he used to read to Allen some 40 years ago: Hurld headlong flaming from th' Ethereal Skie

With hideous ruin and combustion down. . . .

A word is sometimes just beyond his reach, or he falters on a phrase; Allen sits on the couch, body angling toward the gold armchair which holds his father, feeding the correct words when needed, so the two of them complete the passage. Allen has done less formal teaching than his father, but both are marvelous at sharing knowledge and wisdom. When they converse together, they comfortably trade teacher and student roles.

And not in utter nakedness,

But trailing clouds of glory do we come

From God who is our home.

Allen recalls that the other day Louis said this image was "correct, but not true," and Louis adds that by "correct" he means that it is a "good figure of speech, but I don't think it's true."“What of immortality?” Allen questions Louis about heaven, and Louis says it is "wishful thinking."

"What about hell, is there a hell?" Allen playfully jabs his words with a smile. Louis doesn't believe in hell, either; he is more interested in talking about the awe and wonders of the galaxies. "Why this prodigious display of energy?" Eventually stars burn up. "You wonder what it's all for."

"That's pretty cheerful," Allen replies, "because that leaves us completely free to do whatever we want in a closed dream system."

Louis has been mulling all this over. He starts to build something out of the fragments of talk: "Thinking really is poetry, although we don't call it poetry," he says, establishing the teacher role.

"Thinking is poetry?" questions Allen, the student.

“All kinds of thoughts are mental constructs," answers Louis, referring to such concepts as heaven and hell, adding, "In poetry you have a mental construct, but you have someoriginality of language that startles you" (like ‘trailing clouds of glory’). "Every metaphor, every figure of speech is a new construct."

"That's the first time I ever heard you say that all thoughts are poetry."

In the dialogue that ensues, Louis makes the point that, like poets, scientists construct images which may or may not hold up as true, such as the concept of "atom," which is derived from the Greek, meaning "not cut." This concept was proved to be untrue, and a new "thought/poem" had to be created.

Allen did not know the derivation of the word "atom" and asks Louis to repeat it. Louis continued as teacher, explaining that the nucleus is made of quarks. Like a playful student, Allen shouts with glee a duck-like, "Quark Quark! The answer is quark, quark, like Lewis Carroll." He soon shifts into the teacher role to explain that what Louis has been saying is similar to the Buddhist concept that all conceptions of the existence or nonexistence of God or self are equally arbitrary.

"I would agree to that," Louis replies.

“The decay of the body,” Allen continues, “underlines the arbitrary nature of the idea of self.”

“I know,” Louis says softly.

“Throughout the conversation, Louis looks at his watch every few minutes. He seems to have a purpose for it, though I know he is not expecting anyone. Each look at the watch is inconclusive, till finally, with surety, he hands it delicately to Allen, saying, "Allen, will you wind this up."

"It's now 10 of 11, Louie, so it just stopped, your watch just stopped 10 minutes ago."

Allen tapes many conversations with his father, including: recollections ofPaul Robeson at Rutgers; conversation about his grandson (Allen's brother, Eugene, a lawyer and a poet, has four children); description by Edith of a visit to Dr. Levy; Louis reading his early poem, “The Poet Defies Death”; recollections of a recently deceased friend; conversation on Book Two of “Paradise Lost”; and Louis having a dizzy spell. Allen also sketches his thoughts and dreams about his father into his journal (which provides the raw material for his books. Periodically, Allen goes through the journal, picking off the “cream”). In the black-covered, lined notebook with “Record” printed on the cover, Allen entered the following on May 18, 1976, after he and his father had read Wordsworth together (“With tranquil restoration:—feelings too / of unremembered pleasure….”)

Wasted arms, feeble knees

80-years-old, hair thin & white

cheek bonier than I’d remembered—

head bowed on his neck, eyes opened

now and then, he listened—

I read my father Wordsworth’s ‘Tintern Abbey’

“When I was a boy we had a house

on Boyd Street—” —“Newark?”

“Yes, the house was near a big empty lot,

full of bushes and trees. I always wondered

what was behind all those green branches

and tall grass. When I grew up

I walked around the block

and found out what was back there—

it was a glue factory.”

Allen reads the journal entry to his father, introducing it by saying, "I wrotethis down, I don't think you've seen it." He refers to it as, "my latest poem," but corrects himself by saying, "ours," before reading it.

As Louis listens, he is in the same posture as Allen describes. He nods at the accuracy of his son's words, which capture the approach he's used for much of his poetry writing: "I will see a flash of the past; suddenly it'll swim into my ken some picture of that incident. Like starpoints, when you're far away from them you can see the pattern."

One of Allen's dreams about his father, from an April journal entry:

"Louis was in bed in front room of Park Avenue apartment. I was with Edith by his side. He slumped over on the bed, eyes closed. I put my palm to his forehead and held him close, hugging him. Ah a tremor in his chest near his heart, a few spasmodic movements deep inside his body. I said, ‘Ah,' clearly to him as if the vibration of my voice through my hands or into his ears might be heard far off as a sign of openness. Ah he was still alive, that his movement hadn't ceased, very subtle stirrings still, though breath seemed to have stopped. Ah. Edith sat by attentive silent."

"Ah" is a Buddhist mantra meaning "appreciation of present, endless space."

One of Louis's last poems says that "somewhere" there is a tree and a patch of dirt which will be made into a coffin and grave for him; but he is “patient.” "When you get older and you're seriously ill, you think of these things," he comments about the poem, which he has paraphrased from memory because his only copy was submitted for publication.

***

·At midday—after a morning of conversation, a nap, and lunch prepared by Allen, Louis is beginning to wear down. He is more grounded in his chair, holding tighter to thearmrests. One must speak louder and more distinctly, and I find that I too am wearing down and have trouble speaking loud enough. I am beginning to withdraw from Louis, perhaps because the seriousness of his condition—which was an abstraction when I agreed to do this article—has seeped into me and I am beginning to feel a closeness to him. But Allen breaks my slipping away by yelling “Louder!" tempering his voice with a playful laugh. It works; as I continue speaking, Louis has less trouble hearing me. I am back with him. But soon it is time for him to return to bed.

"In the afternoon," Louis explains, "a lethargy enfolds me and I want to lie down."

Allen wants to know. "What does it feel like, exactly?"

“It plagues me to close my eyes and relax my body. It embezzles my will."

"Do you have any pain?"

"No pain, that's the fortunate part of this, to give it a light name, infection. If any questions arise, I won't be sleeping, I'll just be lying down in my study, so you can come inand if I don't know the answer, that doesn't stop me from talking."

After Louis goes inside, I think about my momentary withdrawal a few minutes ago, and ask Allen how he and Louis related to the news of his condition. How was he told? How did he face it? Was there any panic on Allen's part?

The only panic, according to Allen, was during the limbo before Louis was told of the doctor's diagnosis, after the family already knew. "I was in a panic that the lack of communication would grow to a point where it would be insoluble. We'd all be trapped in a series of illusions." Louis had been worried that he might have a tumor in his head because he had trouble holding it up (“It felt like my head was falling off"), so when he was eventually told that there was a malignant tumor in his spleen/liver area, he responded with relief that it wasn't as bad as he'd fantasized. In fact, he made a joke about it. Louis has been contributing puns to a local newspaper for many years, one of his most notorious being, “Is life worth living? / It depends on the liver." After he was told of the diagnosis, he said, “I never thought my pun would come back to bite me."

Before Louis was told of his condition, Allen's "pain was in worrying about him, not realizing he could take care of himself; the pain was in projecting our own fears. This is the one time you can really totally communicate. Some of my relatives said they wouldn't want to know ifthey were going to I die. I was really shocked. When I told my father of the delay, he said, 'Ah, so you kept a secret from me.' He marveled that we were so . . . so. . . “ Allen sifts through words in his head before coming up with the right one: "foolish."

***

The day before I visited was Allen's birthday. “It’s interesting to relate to because he's 80 and I'm 50.” He spent his birthday in the studio recording an album of his songs—“It’s great to be 50 and up there shaking my ass making rock and rollwith a bunch of 19- year-old musicians." Allen would hope that his recent flowering in new creative areas and his relationship with his father could be a model that would partially offset what he calls "ageism” among some young people who believe that “everything is shit and people grow old and they can't do anything anymore and they lose their balls and life is just 'kicks.’ That just develops a punk attitude rather than a wise man attitude. It cuts ground from under unborn feet."

With his father, "a very old, natural situation has developed, where we're both so soft and tender to each other.”

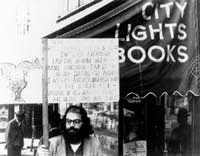

Is it surprising to hear Allen Ginsberg talkso "conservatively" about family and wisdom of the old? It may be surprising, says Allen, if your information about him comes from the "CIA FBI Time magazine stereotype of dirty unwashed evil beatniks eschewing their parents." It is not surprising to Louis, who says, "Contrary to what people thought, that Allen was a Wild Man of Borneo, he's really compassionate." Although Allen never totally broke away from his family, there was a time when he was drifting. But even then, while Allen was moving quickly—living the life he and his friends made their reputations writing about—Louis set up a room for Allen in the house he and his new wife moved into. “Allen picked his own wallpaper, Oriental. . . . In the course of a life, the youngster doesn't want to be tied by strings to the family, so Allen started to wander, but he always had a place to come and get what he needed.” In one visit, Allen brought Jack Kerouac,Gregory Corso, and Peter Orlovsky and they all typed up poems for “Combustion," the first mimeographed poetry magazine. Allen typed up the first section of “Kaddish.” For Allen, full disclosure has been his poetic mode, and perhaps the fullest of his disclosures was“Kaddish,” his classic rhapsodic explosion of words about the insanity and death of his mother, Naomi. Louis was part of that experience and therefore part of the poem. Even though Louis has been happily remarried for 25 years, he is frozen in the minds of tens of thousands of readers as the confused, helpless husband: Louis in pyjamas listening to phone, frightened—do now?—Who could know? my fault, delivering

her to solitude? sitting the dark room on the sofa, trembling, to figure out—

I ask Louis how it felt to see the play version of "Kaddish” a few years ago.

“It was a novel experience. Here I was listening to words that I spoke 40 years ago. My curiosity held my feelings of grief at bay." But this is so far away, that Louis does not want to dwell on it. "You can make mention of these things, but not too much, because that's an era that's passed."

Now Louis sits straight in his chair and talks about the different approaches he and Allen took in dealing poetically with that time. “My first wife died: in my book there are some love poems—Allen wrote 'Kaddish,' which is more first hand. I used what you call 'aesthetic distance.' Let's say I'd go to the sanitarium where she'd be, I’d write: 'the father and two sons observed the wife sick.' Maybe I'm introverted, I don't want to wear my sorrow on my sleeve, but Allen speaks right out. I think one of Allen's strengths is that he has said what young people think but are afraid to say." But for Louis, “sometimes a side blow or a hint is better than the forthright exact sentence."

In the case of "Kaddish," it was painful for Louis and the family to see parts of it in print, but Louis I feels its function for Allen was to “exorcise and give vent to his feelings, so sorrow was eased and there was solace." Louis seems accepting of the difference in their presentations, but what was more difficult was that Allen had been away from home a lot in the midst of the turmoil over Naomi's condition.

"There was a time when my wife was in the sanitarium and Allen was roaming, I thought he was fleeing from sadness, running away from a tragedy."

Allen returns to the room from a phone call in time to hear the last few words. "What was I running I away from?"

"I said you were running away from tragedy."

Allen looks at his father and says, "Well, I didn't get very far. Here we are." Although it was said playfully, he reconsiders, "maybe that's overdramatizing."

They set about the process of exploring this conflict by focusing on some lines from Louis's poem, "Still Life," about the time Naomi was in the sanitarium.

No one is in the house but tensions swarm

The mother in a sanitarium broods.

Her sons by traveling try to chloroform

The loss that burrows in their solitudes

And dreams of how her two grieving sons will climb

Up marble stairways through facades of fame.

Allen picks up on the word “facades,” perhaps avoiding the central conflict by saying, “‘Facades’ in the sense of maya, illusion, naturally because all existence is illusionary.” It is Allen the teacher talking and it sounds inappropriate. He eases into a softer tone, “I always thought you liked the fact that I was getting well-known as a poet.”

“I felt sad that you had to run away or hide from a great sorrow.”

“What do you mean, ‘run away’?”

“You went here, there, you went to Colorado, to San Francisco.”

“I didn’t think that I was hiding, I thought that was exploring, going out.”

The circle is not completely closed. They are, however, a bit closer in touch with each other.”

Poets do not usually achieve fame with the general public. And certainly not quickly. Allen Ginsberg got famous quickly. This was due in part to the controversy over the use of obscenities in “Howl.” “We didn’t like obscenity and told him not to use it,” Louis says, adding, with hindsight, “But it wouldn’t be Allen if he didn’t use it.” Louis was supportive during Allen’s legal battles over “Howl” and, “although we were somewhat bewildered by Allen’s soaring into fame, we were delighted.”

Allen interrupts to say, “You always keep speaking of it as fame rather than beauty. I’m mad, that’s not fair.”

Earlier that morning, I sat in Ben and Bob’s coffee shop/candy store down the block, where Louis used to spend a lot of time before his illness. Proprietor Marty Singer recalled that Louis was in “seventh heaven” and “tickled pink” about Allen’s success and the fact that he was a part of it: “The colleges want both of us,” Louis would say with a smile of both a proud father and proud poet.

A photograph in Louis and Edith’s apartment shows the father and son giving a reading at the 92nd St. “Y,” but Allen is lying on a couch with his leg in a cast. Even though he had broken his leg, he refused to cancel the reading because he “didn’t want to disappoint my father.”

***

There was a long time when Allen was not at ease with his father’s poetry. Louis Ginsberg is a lyric poet (“with a modern touch,” he adds) and so was the young Allen Ginsberg. “My early poetry was just like my father’s, same rhyme schemes. I had to deal with my own resentments and discriminations and rebellion against traditional forms which I grew up with.”

His poetic journey took him away from his father’s approach, and along the road he picked up metaphysical, objectivist/imagist, surrealist, dissociative, and Buddhist influences. Then, in the late ‘60s, he had a public reunion with his father’s verse in his introductory essay “Confrontation with Louis Ginsberg’s Poetry” to Louis’s book Morning in Spring. Allen wrote, “I won’t quarrel with his forms anymore: By faithful love he’s made them his own.” Louis Ginsberg’s work is his own. In the process of doing this piece, I too had to confront a style I had set aside. Many gems shine through Louis’s poems, and it is interesting to see how he deals poetically with many of the same themes Allen explores.

Louis is quick to point out that Allen’s latest book,First Blues, uses rhyme. “There was a time when Allen derided regular meter and rhyme. We had arguments. As time went on, he influenced me a little bit. I’ve written some free verse. Maybe I influenced him.” Allen notes that a major difference between his latest rhymes and his earliest is that “I’m singing.” The new poems include music, the original partner for lyric verse. Allen’s handwritten inscription on the copy of “First Blues” he gave his father reads: “Ah for Louis New Years Eve day December 31, 1975 while we’re all still alive a book of rhymed poems ending the poetry war between us….love, Allen.” ***

Louis is lying down on the couch in his study, drifting along a fitful half-sleep. Allen shows me around the room while a few feet away his father is exhaling a steady stream of delicate sighs.

“I gave it to him, it’s his.”

The sighs from the couch gradually change shape to form a word, which eventually reaches Allen as the sound of his name.”

“Allen….”

“Hmmmmmm…what?” Allen answers, hovering over his uncovered father, ready to bring him whatever it is he wants. But he doesn’t want anything, except to say, “Allen, you’re all right.”

“Yeah, I am all right.”

“You’re all right, Allen,” Louis repeats, looking through almost-closed eyes at his son.

“Yeah, I’m all right. You’re all right?”

“You’re all right, I’m all right, you’re all right,” Louis says clearly, completing the conversation.

A few minutes later, Louis says, “Allen, I feel a draft, close the window.”

Allen brings the cover, which he pours over Louis’s body, pausing to hold Louis’s arm for a while, fingers breathing on his father’s flesh.

***

In the living room, while his father is napping, Allen mentions that William Carlos Williams’s widow, Flossie, just died. “I hadn’t, alas, been in touch with her for many years.” We talk about Charles Reznikoff, who died a few months ago. “I wonder who’s keeping Mrs. Reznikoff company,” Allen says. Louis returns from his nap. He wants to know if I have any more questions, and requests that he be sent copies of the article. He sits down and says:

“I was talking before about the constellations and immensity, unfathomable of the universe—are you taking this down?—no matter how small men are, they are greater than the biggest star, because they know how small they are.

“I wanted to complete that thought.”

***Louis visits Allen's Naropa class in 1975 - see here, here and hereHear Charles Ruas' recording from 1968 - "41-year-old Allen Ginsberg introduces his 72-year-old father, Louis, who wryly comments on current affairs of the day and reads his own poetry. The segment ends with audience questions and both Ginsbergs venture from poetry into politics with growing contempt and hostility until the house shuts them down"