America

أمــــــــــــــــــريـــــــــكـــــــــــــا

. أمريكا لقد منحتك كل شيء وها أنا الآن لا شيء

أمريكا، دولارين وسبعة وعشرين سنتيمات،

سبعة عشر ينايرألف وتسع مائة وست وخمسين

. أنا لا أستطيع أن أحافظ على رأيي الخاص

أمريكا متى سننهي الحرب على الإنسانية؟

انكحي نفسك بقنبلتك الذرية!

أنا لا أشعر أنني بحالة جيدة

. لا تزعجني

. لن أكتب قصيدتي حتى يستقيم رأي

أمريكا متى ستصبحين بريئة؟

متى ستخلعين ملابسك؟

متى ستنظرين إلى نفسك من خلال اللحد؟

متى ستكونين جديرة بالمليون تروتسكي الذين يسكنون أرضك ؟

أمريكا لماذا تمتلئ مكتباتك بالدموع؟

أمريكا متى سترسلين بيضك إلى الهند؟

.لقدسئمت من رغباتك المخبولة

متى يمكنني الذهاب الى السوق الممتاز

لأشتري ما أحتاج اليه فقط بمحياي الجميل؟

أمريكا أنا وأنت نمثل الشيء المطلق بعد كل شىيء

. وليس العالم الأخر

. آلاتك تفوق مايلزم بالنسبة الي

. جعلتني أتوق الى أن أصبح قديسا

! يجب أن تكون هناك وسيلة أخرى لتسوية هذه المسألة

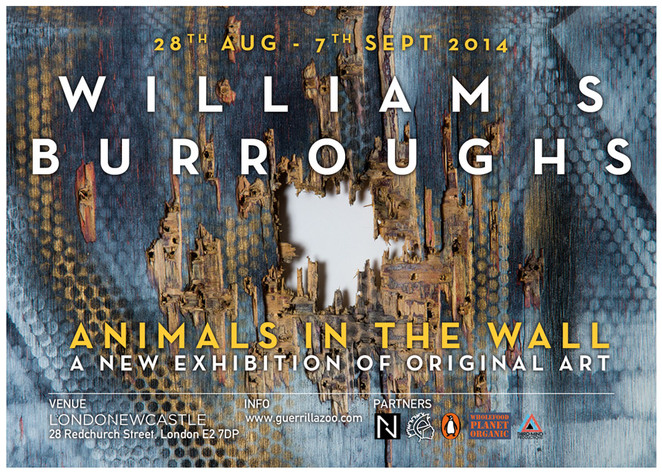

بوروز في مدينة طنجة.

لا أعتقد أنه سوف يعود.

.الأمرأصبح مشؤوما

هل أنت مشؤوم كذلك؟

أوأن المسألة تتعلق بشكل من أشكال النكتة الواقعية ؟

. أنا أحاول أن أصل إلى لب المسألة

. أنا أرفض أن أتخلى عن هاجسي

أمريكا توقفي عن دفعي.

أنا أعرف ما أفعله.

. أمريكا ان أزهار البرقوق تسقط

أنا لم أقرأ الصحف منذ شهور،

. شخص ما يحكم عليه بتهمة القتل كل يوم

أمريكا أنا أتعاطف مع جماعة الوبليين

أمريكا لقد كنت شيوعيا عندما كنت طفلا

. أنا لست آسفا

. أدخن القنب الهندي كلما أتيحت لي الفرصة

أجلس في بيتي لأيام لاتنتهي

. وأحدق في الورود داخل الغرفة

. عندما أذهب إلى الحي الصيني أسكر

لكنني لا أضاجع أحدا.

لقد اتخدت قراري

المتاعب قادمة.

. يجب أن تنظروا الي وأنا أقرء ماركس

. طبيبي النفسي يعتقد أنني تماما على حق

. لن أصلي للرب

. لدي رؤى صوفية واهتزازات كونية

أمريكا لم أخبرك بعد بما فعلته للعم ماكس

.عندما قدم من بلاد الروس

! أنا أخاطبكم

هل ستسمحون لمجلة التايم بأن تديرحياتكم العاطفية ؟

. أنا مهووس بمجلة التايم

. أقرأها كل أسبوع

غلافها يحدق في وجهي

كلما مررت خلسة بدكان السكاكر المنزوي.

. قرأتها في الطابق السفلي لمكتبة بيركلي العامة

كانت تخبرني دائما عن المسؤولية:

رجال الأعمال جديين.

. منتجي الأفلام جديين

. كل الناس جديين باستثنائي

. يخطر لي أنني أمريكا

. أنا أتحدث لنفسي مرة أخرى

. آسيا تنتفض ضدي

. أنا لاأمتلك فرصة الرجل الصيني

. من الأفضل أن أ راجع مواردي الوطنية

مواردي الوطنية تتكون من:

لفافتي قنب هندي،

ملايين الأعضاء التناسلية،

كتب شخصية غير خاضعة للرقابة

تسير بألف و أربع مائة ميل في الساعة.

.وخمسة وعشرين ألف مؤسسة للأمراض العقلية

أنا لن أقول شيئا عن سجوني

ولا عن ملايين المحرومين

الذين يعيشون بأصيص أزهاري

. تحت ضوء خمس مائة شمس

لقد قضيت على دورالدعارة بفرنسا،

. طنجة ستكون محطتي الثانية

طموحي هو أن أكون رئيسا

. بالرغم من أنني كاثوليكي

أمريكا كيف يمكنني

أن أكتب صلاة قدسية

في مزاجك السخيف؟

سأواصل مثل هنري فورد

مقطوعاتي الشعريه فريدة مثل سياراته

الى درجة تجعل منها جنسين مختلفين.

أمريكا سأبيع لك مقطوعاتي الشعرية

بألفين و خمسمائة دولار لكل مقطوعة شعرية.

سأحذف خمسمائة دولار من مقطوعتك القديمة.

أمريكا أطلقي سراح توم موني

أمريكا أنقدي الموالين لإسبانيا

أميركا ساكو وفانزيتي لايجب أن يموتا.

. أمريكا أنا أمثل أبناء سكوتسبورو

أمريكا عندما كنت في السابعة من عمري

كانت أمي تصحبني إلى اجتماعات خلية الشيوعيين

كانوا يبيعوننا الحمص،

حفنة للتذكرة الواحدة

التذكرة تكلف نيكلا

كانت الخطابات مجانية.

كان الكل بريئا وعاطفيا اتجاه العمال

كان الصدق يسود كل شىء

ليست لديك أية فكرة عن طيبة الحزب

في عام 1835 كان سكوت نيرين رجلا مسنا و عظيما

كان صنديدا حقيقيا

جعلتني الأم بلورأبكي

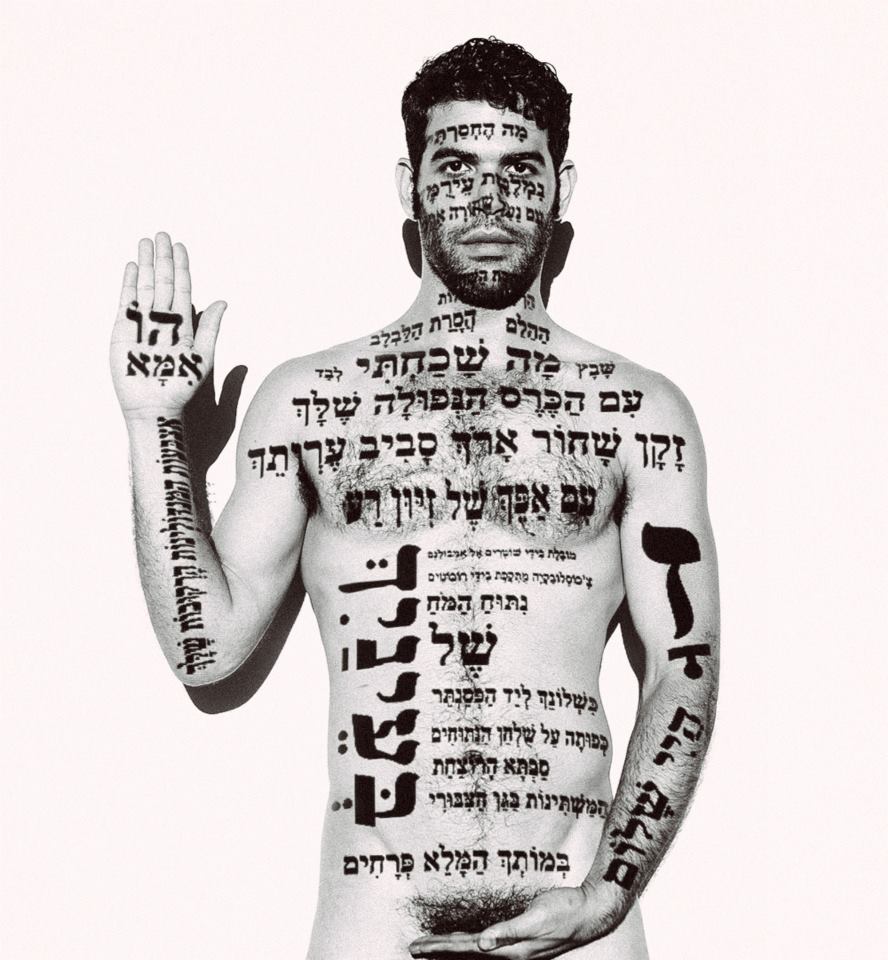

رأيت اسرائيل أمتربسيطا ذات مرة

. من المفترض أن يكون كل شخص جاسوسا

. أمريكا أنت لا تريدين حقا أن تذهبي إلى الحرب

. أمريكا انهم هؤلاء الروس الخبثاء

. هؤلاء الروس، هؤلاء الروس وهؤلاء الصنيون

. هؤلاء الروس

روسيا تريد أن تأكلنا ونحن على قيد الحياة.

سلطة روسيا مجنونة

تريد أن تأخذ سياراتنا من مرائبنا

تريد اللاستيلاء على شيكاغو.

تحتاج الى مجلة ريدرز دايدجيست حمراء.

تريد أن تنقل مصانع سياراتنا الى سيبيريا..

. البيروقراطية الكبرى تشغل محطات غازنا

هذا شيء تشمئز له النفوس!

آ آ آ آ آ آخ!

. روسيا تريد أن تعلم الهنود الحمر القراءة

روسيا تحتاج الى الزنوج الأقوياء.

أأأأه! تريد أن تجعلنا نعمل ستة عشر ساعة كل يوم.

النجدة!

. أمريكا هذا أمر خطير جدا

. أمريكا هذا هو الانطباع الذي أحس به من خلال مشاهدة التلفاز

أمريكا هل هذا صحيح؟

. من الأفضل لي أن أتوجه مباشرة إلى العمل

فأنا لا أريد الانضمام إلى الجيش

أو إيقاف المخارط في مصانع الأجزاء الدقيقة،

. أنا على أي حال قصرالبصر ومريض نفسيا

أمريكا، أنا أضع كتفي العليل على العجلة.

- بيركلي، 17 يناير 1956

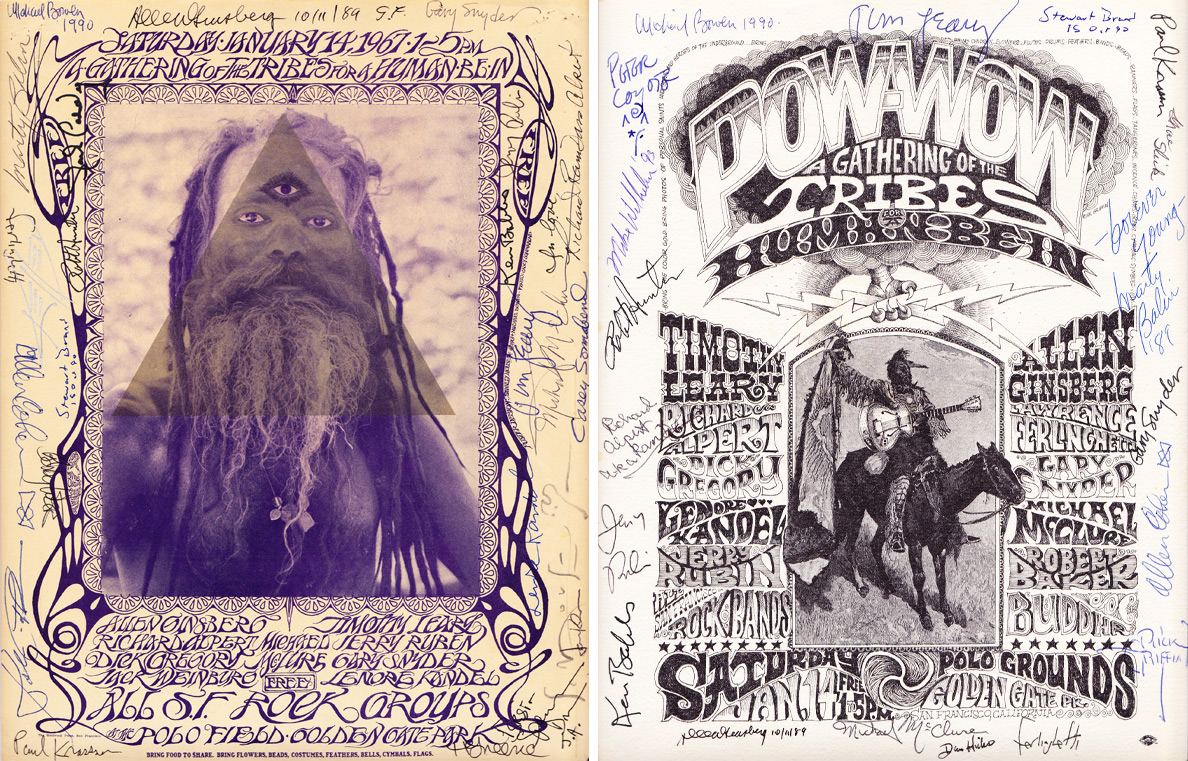

من ديوان 1947-1980 لألين جينسبيرج، الذي نشرته هاربر ورو

حقوق الطبع والنشر © 1984 لألين جينسبيرج