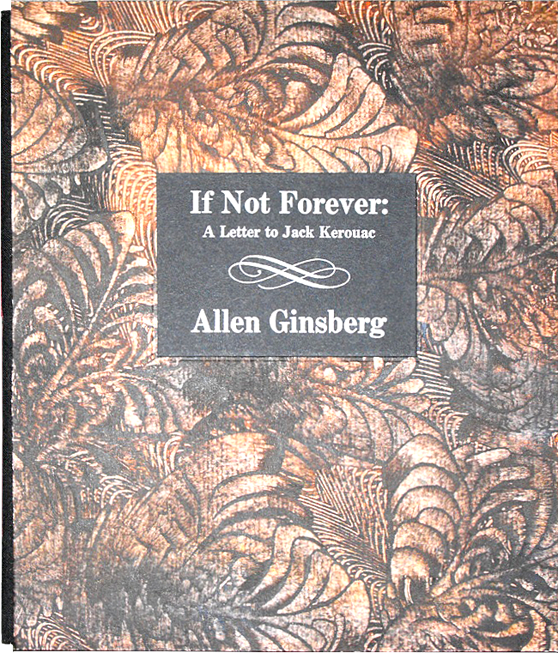

A rare (rarely-seen) Ginsberg item (that didn't meet its estimated price in their last big Beat-related auction) - If Not Forever - A Letter to Jack Kerouac(Sore Dove Press, San Francisco, 2008) - went up again on the auction block at the PBA Galleries in San Francisco yesterday (alongside a number of other Ginsberg and Beat-related pieces, the residue, second culling, (third culling, actually) from Rick Synchev's fabled "Beats, Counter-Culture, and the Avant-Garde" collection.

A couple more highlights - (likewise from Sore Dove, 2011), Poem ("Prophecy" ("Prophecy if I shall find/What I miss..") (first publication, with original art by Soheyl Dahl)

a miscellaneous collection of Ginsberg books

&Bill Morgan (and Bob Rosenthal's) hommage volume (from 1986) Best Minds

On Wednesday in Berkeley at Mrs Dalloway's bookstore, poet and actor, Ian Hirsch recited all of Howl Part 1 from memory.

Speaking of San Francisco, here's Allen Ginsberg performing in San Francisco in November of 1981 (alongside Marc Olmsted, Dan Rielly, Gary Schwantes, Bruce Slesinger and Tom Latta - "The Job") - his ever-timely classic, "Birdbrain"

[Allen Ginsberg and Marc Olmsted (of "The Job"), San Francisco, 1981 - Photograph by Marc Geller]

Tomorrow night in New York atThe Stone, Bruce Andrews and Charles Bernstein

sometime editors of L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E magazinepresent a B=U=R=R=O=U=G=H=S tribute.

More Burroughs NYC celebrations in the coming weeks.

Meanwhile, in the National Museum in Wales...

[Allen reading from "Wales Visitation" (September, 1968, on the William Buckley "Firing Line" t.v. programme) - installation, part of the exhibition, "Wales Visitation - Poetry, Romanticism and Myth in Art", currently at the National Museum of Wales, Cardiff - on through to September 7 - Photograph - Alex Martin]