["Rarely, Rarely, Comest Thou Spirit of Delight (Portrait of Keats and Shelley)"- Gregory Corso, c.1994, (31 1/2" x 35"), oil on canvas board; (originally collection of Allen Ginsberg)]

AG: Those who studied with me before or who have worked with me before, this may be repeating some matter. Has anybody here read Shelley's "Adonais"? Can you raise your hand? Has anybody here not ever heard of it? Raise your hand if you haven't. Come on, you never heard of it there. So raise (your hand). You never heard of it, did you? Okay. So you can raise your hand safely, then. It's safe to raise your hand if you haven't heard of it. Nobody's going to judge you. Okay, It's his lament for John Keats, his beloved far-distant friend. He's talking about where you can find Adonais, or Keats, where you can find his tomb. And it's the forty-seventh stanza - so I'll read stanzas forty-seven to fifty-five. [Allen begins reading from Shelley's "Adonais", beginning from stanza forty seven - "Who mourns for Adonais? Oh, come forth,/Fond wretch! and know thyself and him aright./Clasp with thy panting soul the pendulous Earth;/As from a center, dart thy spirit's light/Beyond all worlds, until its spacious might/Satiate the void circumference: then shrink/Even to a point within our day and night;/And keep thy heart light lest it make thee sink/When hope has kindled hope, and lured thee to the brink" - through to stanza fifty-five - "The breath whose might I have invoked in song/Descends on me; my spirit's bark is driven,/Far from the shore, far from the trembling throng/Whose sails were never to the tempest given;/The massy earth and sphered skies are riven!/I am borne darkly, fearfully, afar;/Whilst burning through the inmost veil of Heaven,/The soul of Adonais, like a star, Beacons from the abode where the Eternal are."] - Okay. The breath. (the reason I was shouting was that there are people back there who are gossiping and blabbing, so I was just trying to bring their attention back to the subject).

Student: Oh, God.

AG: Excuse me.

Student: That was beautiful.

AG: The reason I was shouting about "death" and "die" and "die" - "drop dead", was what (I was saying).

Student: (Sorry)

AG: The point here is breath. The point, finally, is that here, at the height of inspiration, of the most inspired, angelical poet, Shelley, the ultimate subject finally comes to be breath itself. In a lot of high poetry you find that to be so. So when we begin with the breath, on a lowly level of just paying attention to our own breath, as the beginning of poetics, and as well as the intersection of poetics and meditation, then actually we're beginning with the first and last subject. Or the first and last process, or the first and last operation of poetics, which is breath.

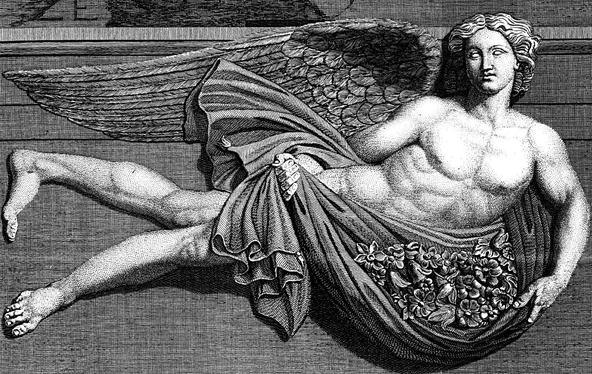

[Zephyrus - Greek God of the West Wind]

The other text by Shelley which deals with ... (what time is it? Yeah). (The other text) that deals with breath is "Ode to the West Wind". How many people know that? Is there anybody that has not seen that yet? It's safe to raise to your hand. So let's find that. I'll read that more evenly, as long as people will stay with this particular breath. In other words, I'm trying to trace a breath through the poem -a relatively subtle matter. So I'm asking, to some extent, for attention to that - undistracted attention to the breath of the poem.

So the west wind is actually the breath of change, as breath also is change, destruction - Shiva, for those of (you) who are Hindu-oriented. This particular breath. [Allen proceeds to read, in its entirety, Shelley's "Ode to the West Wind" - " O wild West Wind, thou breath of Autumn's being,/Thou, from whose unseen presence the leaves dead/Are driven, like ghosts from an enchanter fleeing…"…" Drive my dead thoughts over the universe/Like withered leaves to quicken a new birth!/And, by the incantation of this verse,/Scatter as from an unextinguished hearth/Ashes and sparks, my words among mankind!/Be through my lips to unawakened earth/The trumpet of a prophecy! O Wind,/If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?"] - Okay. So there's breath again.

Shelley is considered the most angelically inspired poet. The most romantic of all poets. Except for Rimbaud, perhaps the most luminous, angelical of all the poets. Or as Matthew Arnold said, “a luminous and ineffectual angel beating his wings in the void in vain”. [Editorial note – the exact quote is “ a beautiful and ineffectual angel beating in the void his luminous wings in vain”]. However, he's actually more effectual an angel than Matthew Arnold, because Arnold had no such breath as Shelley. Shelley really did have this angelic breath. So, why was Shelley so good? Because he had that breath. Because he had the ear for that breath. And you'll find it in a lot of heroic poetry. So we'll find breath from the most ordinary mind poetry, like William Carlos Williams, to the most advanced outpouring ecstatic. So, through this course, then, I guess, the key, or the common activity, will be breath and its vocalization. So let's quit for now.