Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

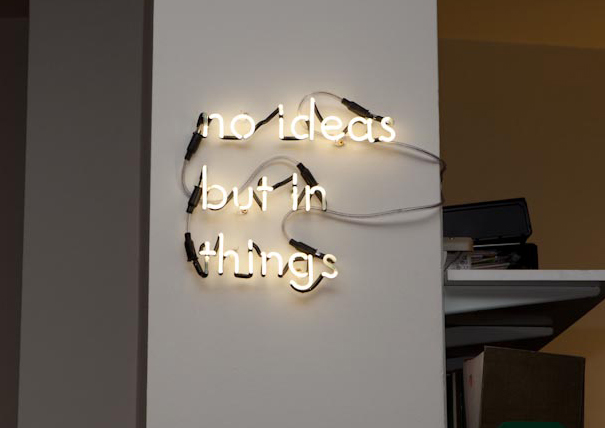

["No ideas but in things" - Simon Cutts (1909) neon manifestation of William Carlos Williams' imperative]

AG: Yeah?

Student: In that credo of his [William Carlos Williams'] that everybody's heard so many times - "No ideas but in things'

AG: Um-hmm

Student: …when you said that you were going to do Williams for this, the first thing I thought about..

AG: Um-hmm

Student: …was relating that answer to the Buddhist answer of no things, just like you cut out…

AG: The Buddhist what?

Student: I was wondering about relating it to that statement.

AG: Relating the statement "No ideas but in things" to what?

Student: (To) nothingness. Without the ideas in it. Like, emptiness..

AG: Well, could you give a Buddhist phrase that would capture that? Rather than just the word "emptiness"? Is there a way of doing that?

Student: (If I were asked), first, I'd go for the "Form is Emptiness" thing [Editorial note - the reference is, of course to the Pranaparamita Sutra (the Heart Sutra) - "Form is not different from emptiness, emptiness, not different from form"). There's the..

Student 2 : No it wasn't empty…

AG: Well, we're going to get a little off-track if we get into this right now. We're still on the breath, still on the breath. We haven't even moved from the breath yet. We're still breathing. Is everybody still breathing? Everybody here still breathing? How many forgot that they were breathing. I did. Okay, but now we remember again that we were breathing. Okay, so that's really the whole process - remembering that you're breathing, or remembering that you're here, even. Because we all get lost in the ideas, see? So we space-out into an idea-realm. And then, occasionally, are reminded to come back to our own presence with the ongoing breathing and the ongoing thinking - both - instead of getting lost in the thought, like dream, spacing-out into the thought, going on a long trip with the thought, and then waking up from the thought, after the class is over, maybe.

So, to some extent, we'll try to keep waking up during the class, and, as you wake up, you might be able to remember the thought that just got dropped - whether it's an iron horse, or an air horse. or a cock horse, or a cloud horse, or no horse..but just teeth. Whatever it was, whatever you remember just before you woke up, you might keep a notebook and write that down during the course, a notebook which would just be the tail-ends of the last thoughts you had , when you were waking up, during the class period. Is that clear, these class instructions. So we'll be trying to write poetry in the class, and so…

Student: Allen?

AG: Wait a minute, let me finish my thought here. We'll try to capture the last thoughts, or not (capture) (well, “capture”'s the wrong word). As you wake up from daydreams, if there's anything left off, substantial, in residue, in language, picture, smell or anything, get a little phrase of it. More extensive or less, but just a little phrase, like when you wake up in the morning and you've had a conversation with Bob Dylan that's been very pleasant, just write down "talking with Bob Dylan", or whatever it was, whatever the situation, if you can remember a phrase or two. So what you might do is keep some separate, clean pages in your notebook for just entering the thoughts, so that, at the end of the course, you'll have a whole collage of images from your thought-world, that you'll be waking up from during the class (and you might sneak some phrases in from every walking… or waking up in your bed, too, if you want, but mainly keep it for here).

Student: How is this different from writing dreams? which are not allowed.

AG: This is writing day-dreams. Which are not allowed?

Student: Right.

AG: Who said you're not allowed to write dreams?

Student: You did.

Student 2: You did.

AG: I said you're not allowed to write (dreams)? Oh, I see.

Student 2: You're a dreamer!

AG: Oh, oh, oh, oh. Well, I'm contradicting myself. I was dreaming.

Student 2: Two different kinds.

AG: Okay, but (what) I was pointing out (was).., the difference was.. you're waking up from a dream, so you'll be able to deal with it as a dream, or as an object, like it's furniture, like you describe this as a piece of furniture, you've just had the thought of.. whatever you've had the thought. You just had the thought of the venetian blinds and the breeze going through the room. That's an object. That thought in your head is a piece of furniture once you look at it. Once you look at it objectively. Once you wake up from it, so to speak. It's just another thing in the world, like anything else. Just because it's in your head doesn't mean it, it wasn't ...

Student: Unrateable?

AG: Yeah. So that you can treat your thoughts as if they were objects. Dig? Does that make any sense?

Student: No.

AG: You can get lost in your thoughts, and say "I am a great poet. I'm going to write a poem about (how) I'm a great poet, and I'm gonna ..." and on and on and on – or, you can look at yourself doing that and then write it down with some humor. Right? So there's a difference between getting lost in your thought and not recognizing that it's just a thought, or (and) seeing all its forms and seeing how precise it was and seeing how pretty it was and all the little flowers surrounding it and the second and third thoughts that went along with it, and the ones that came before it, and the possible logical extensions of it, and having fun with it. But not getting trapped in it. It's not quite being detached, it's just recognizing it and appreciating it. Appreciating it.